How the Housing Bust Widened the Wealth Gap for Communities of Color

When the housing market went bust, homes in communities of color were more likely to succumb to foreclosure than homes in white communities.

When the housing market went bust, homes in communities of color were more likely to succumb to foreclosure than homes in white communities.

When the housing market went bust, homes in communities of color were disproportionately more likely to succumb to foreclosure than homes in white communities. These homeowners not only lost their biggest asset—their home—but they also missed out on the opportunity to amass wealth throughout the subsequent recovery as home values climbed back upward.

At the same time, those who were able to hold onto their homes through the worst of the housing bust have mostly seen their wealth increase as their homes’ values have largely surpassed their housing-bubble peaks. This difference in fortunes, both literal and figurative, across racial and ethnic communities illustrates the ways in which the Great Recession helped exacerbate wealth inequality.

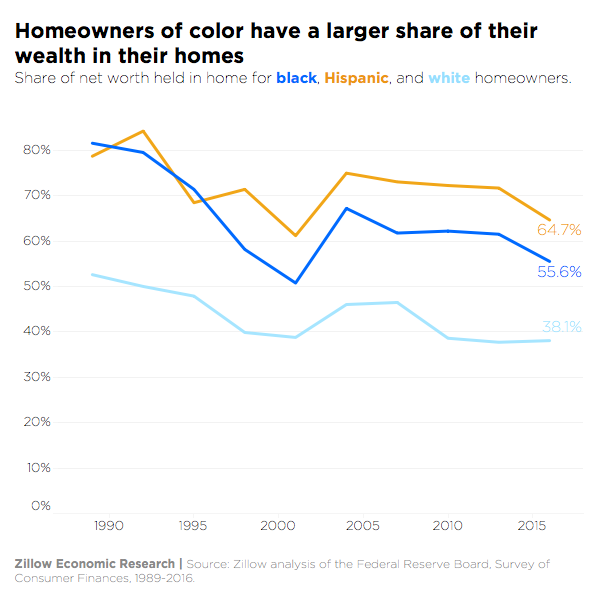

For most people, a home is the single largest asset they own in their lifetime. In 2016,[1] a home accounted for just over half (42.1%) of the typical U.S. homeowner’s total wealth. But for homeowners of color, their home has and continues to account for a much larger share of their net worth. For the typical Hispanic and black homeowner, their home accounts for the majority of their wealth (64.7% and 55.6%, respectively), while a home accounts for just over a third (38.1%) for the typical white homeowner.

In 2007, near the height of the housing bubble, a home accounted for 73.1% and 61.8% of the typical Hispanic and black homeowner’s total wealth, respectively, compared with just 46.5% for the typical white homeowner. Since their homes accounted for such a large share of their wealth, homeowners of color were more exposed to the foreclosure crisis that accompanied the housing market crash as home values plummeted. With fewer assets to draw on, it was harder for them to hold onto their homes if and when their homes fell underwater—meaning, they owed more on their homes than the homes themselves were worth.

As home values fell after the housing bubble popped, homes in communities of color were more likely to be foreclosed upon than white communities.[2] Of all the homes foreclosed upon between January 2007 and December 2015,[3] 12.7% and 19.4% occurred in predominantly black and Hispanic communities, respectively. To put that into perspective, only 7.7% and 9.6% of all homes are located in predominantly black and Hispanic communities. Whites, however, fared better—66.4% of all foreclosures occurred in predominantly white communities. While that may sound like a high share of all foreclosures, it’s because the vast majority of homes (81.2%) are located in predominantly white communities.[4] In other words, homes in black and Hispanic communities were 2 and 2.5 times as likely to succumb to foreclosure as homes in white communities.

In certain metro areas, communities of color fared even worse. In San Francisco, for example, 4.6% and 38.1% of housing bust foreclosures occurred in black and Hispanic communities, respectively, compared with 43.5% in white communities. To put this into perspective, just 2% and 16.5% of all homes in San Francisco metro area are located in black and Hispanic communities, while 62.3% of all homes are in white communities. Together, this means that black and Hispanic communities experienced a rate of foreclosure that was 3.3 times as high as white communities.

Part of the reason that homes in communities of color experienced higher rates of foreclosure is because home values plunged more dramatically in those areas during the recession. As home values fell, negative equity—when a home is worth less than the amount owed on it, making it difficult if not impossible to sell or refinance—skyrocketed. Homeowners in negative equity are more likely to be foreclosed upon, especially those in deep negative equity that might see little point in throwing good money after bad just to stay in a home they may realistically have little to no hope of one day selling for a profit.

As the recession continued to unfold, layoffs and unemployment spiked, which left many people out of work for years and forced others to accept lower-paying jobs than they previously held just to make ends meet. This was especially damaging for people of color, many of whom typically have a more difficult time absorbing financial shocks like loss of employment and unexpected expenses. Just over a third of blacks and Hispanics (35% and 38.2%, respectively) have an emergency or rainy day fund that would cover their expenses for three months in case of sickness, job loss, economic downturn or some other emergency. For whites, that figure is 55.2%.[5] Part of the reason for the disparity is that blacks and Hispanics earn less than whites, at the national level.

Foreclosure does more than strip the title of a home away from a homeowner: It also strips away any and all wealth a homeowner had in the home, both invested up front in the form of a down payment and accumulated over time through home value appreciation and built-up equity. In the lead-up to the housing bubble, homeownership peaked for all races and ethnicities, making the subsequent crash and foreclosure crisis even more devastating for newly minted homeowners.

Those who lost their homes to foreclosure also were forced to re-enter the housing market as renters. The sudden new demand for rental housing caused rents to soar throughout the recession, so homeowners that were foreclosed upon—regardless of racial or ethnic group—were putting a larger portion of their income towards rent every month. But communities of color took the largest hit: The typical renter of color spent upwards of 40% of their income on rent each month. Even worse, these once-homeowners were never able to realize the sometimes huge increases in their homes’ values during the recovery.

Homes that succumbed to foreclosure fell dramatically in value. Foreclosed homes in black and Hispanic communities lost more than half (54.5% and 59.2%, respectively) of their value from the height of the housing boom to the bottom of the crash. Foreclosed homes in white communities fared slightly better—falling in value by 35.8%. For comparison, the typical (that is, not foreclosed) home nationwide lost just over a quarter of its value (25.8%).

After the national housing market hit bottom, home values started rising quickly again across the board. Although the typical foreclosed home in communities of color has yet to return to its housing-bubble peak, it has more than doubled in value throughout the recovery, growing 109.2% and 122% in black and Hispanic communities, respectively. Foreclosed homes in white communities have also experienced tremendous, though less precipitous, growth (71.6%), and are currently worth 10.1% more than they were during the peak of the bubble. Over the same time, the typical U.S. home—which didn’t succumb to foreclosure—grew 52.5% and is currently worth 13.1% more than it was before the recession. The values of foreclosed homes in communities of color continue to grow—at a whopping 20.2% over the past year in predominantly black communities and 9.1% in largely Hispanic communities, even as the national housing market slows to 6.6% year-over-year, which is a testament to all of the value—and wealth—those once-homeowners could have earned.

In some of the large markets that have had very robust recoveries, the values of foreclosed homes in communities of color have far surpassed their pre-recession peaks. In Los Angeles, foreclosed homes in black and Hispanic communities are currently worth 12.6% and 1.7% more than they were at the peak of the bubble. In Atlanta, these homes are worth 2.1% and 24.5% more, respectively.

If foreclosed homeowners had been able to hold on, they would have been able to see their home’s equity – and therefore their wealth – increase. For homeowners of color, this would have been a large share of their wealth.

And finally, even if a previously foreclosed-upon homeowner had been able to accumulate new wealth through savings or other assets after their foreclosure, laws often prohibited many of them from reinvesting that wealth back into housing for seven years, thereby causing them to miss out on large gains in home values over the past several years.

Wealth inequality and racial disparities have been at the forefront of discussion as the nation climbs out of one of its greatest recessionary periods, and for good reason. The gap across racial and ethnic lines in the U.S. worsened throughout the housing bust and foreclosure crisis that followed, as millions lost not only the roof over their heads, but the wealth – and the opportunity to potentially build more – that came with it.

Zillow identified racial and ethnic communities at the census-tract level based on racial pluralities. Once census tracts were categorized as predominantly black, Hispanic, or white, we mapped Zillow’s proprietary dataset of home values and housing information to these communities to identify where foreclosures occurred between January 2007 and December 2015. We also tracked changes in home values over time. We then aggregated census tracts up to the metropolitan area and national level.

[1] The latest year for which data from the Survey of Consumer Finances is available.

[2] This research focuses on communities that are predominantly black or Hispanic (collectively, “communities of color”) or white. The U.S. Census Bureau also provides data on other racial groups like Asians, but given their relatively small share of the population, they have mostly been excluded from this analysis.

[3] This analysis focuses on foreclosures between January 2007 and December 2015 to encapsulate the period when foreclosure rates were highest. Prior to the bust, U.S. median home values peaked in May 2007, but the peak was earlier in some markets. Similarly, even though the national housing market bottomed out in February 2012, the impact of the bust and recession lasted much longer. Homeowners who attempted to hold onto their homes throughout the recovery were sometimes unsuccessful, which continued the trajectory of steady foreclosures through 2015. In 2016, foreclosure rates began to level off, signaling the end of the foreclosure crisis.

[4] This analysis does not suggest that black or Hispanic residents—or residents of some other race—can’t or don’t live in largely white communities, or vice versa; they certainly can, and almost always do. In fact, this is true in 99.5% of all predominantly white communities across America. However, in the 72,725 communities analyzed, 75% were considered to be predominantly white, 10.3% predominantly black, and 12.7% predominantly Hispanic. The remaining share of communities were classified as either predominantly Asian/Pacific Islander or some other race. Because so many more communities are classified as predominantly white, it follows that so many more homes themselves would also lie within these communities.

[5] Zillow analysis of the Survey of Household Economics and Decision-making, 2017.