A debt ceiling default would send the U.S. housing market back into a deep freeze

A debt default is very unlikely, but new scenario projections from Zillow show sales would decrease sharply as mortgage costs balloon

A debt default is very unlikely, but new scenario projections from Zillow show sales would decrease sharply as mortgage costs balloon

The U.S. federal government is inching closer to a potential default on the national debt since, at the time of this note’s publication, Congress still has not passed legislation raising the statutory debt ceiling. The “X-date” – the date on which the Treasury can no longer meet its obligations without raising debt in excess of the ceiling – is projected to land as early as June, but almost certainly by August, depending on the flow of income tax receipts this spring.

The U.S. has never before defaulted on its sovereign debt, and it is difficult to find historical analogies to such an event. Nonetheless, in order to highlight the importance of averting such a self-inflicted disaster, economic forecasters have attempted to model the impact on the economy if it were to come to pass. In this brief, we sketch out one potential scenario for how a default could affect the housing market, in particular.

Estimates of the effect of a debt default depend a great deal on assumptions about the duration of the event, which is especially hard to predict. Even though a short default would be enough to inflict a tremendous amount of economic damage, that’s no reason to count on it being a short one – the political gridlock that resulted in default, in such a scenario, can’t just be assumed to dissolve after passing the X-date. This scenario models a protracted default crisis.

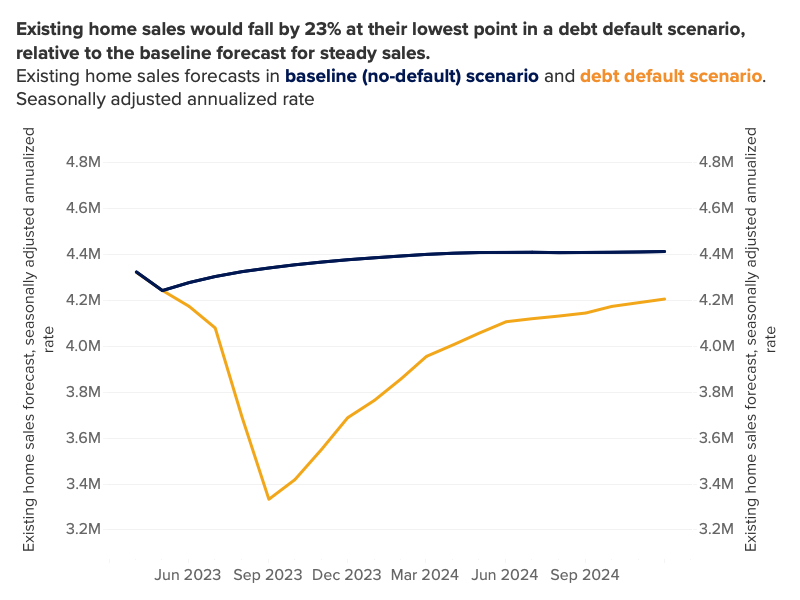

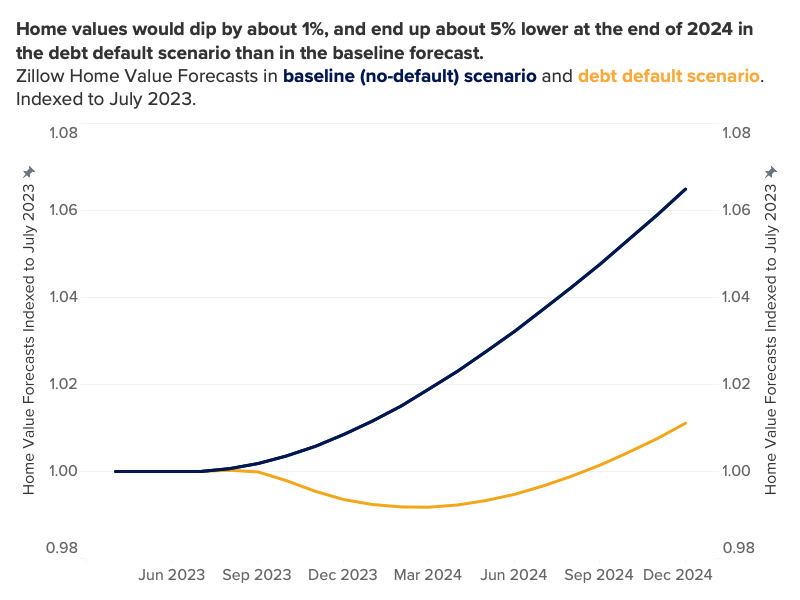

When we forecast the evolution of the housing market over the next 18 months in the event of such a debt default, we estimate that existing home sales would fall as much as 23% relative to the no-default baseline forecast later this year, and that home values may be 5% lower at the end of 2024 than expected in the no-default scenario.

If the U.S. were to enter default in the coming months, one near-certain consequence would be rising debt yields and interest rates. U.S. Treasury Bills (T-bills) provide some of the bedrock and benchmarks for “risk-free assets” on which the economy and most financial models depend. Introducing default risk, or at least the risk of delayed coupon payments, would be like an earthquake rattling that bedrock assumption, sending ripples through the financial system and causing investors to question the safety not just of T-bills but other assets as well. Critically for the housing market, the interest rates on mortgages would almost certainly rise in concert.

The approaching debt ceiling crisis is already causing jitters in some bond markets. One measure of uncertainty is the rising spread between short-term T-bills. The spread of three-month Treasury yields over one-month Treasury yields reached a remarkable high of 1.78 percentage points on April 21. The previous five-year high for this measure was a mere 0.79 points in October 2022. The gap suggests that investors were requiring much higher interest rates on debt maturing this summer, compared to debt maturing in May, likely due to the risk of delayed or reduced repayment in the event that Treasury hits the X-date without Congressional action on the debt ceiling. Now, in early May, 1-month Treasury yields have skyrocketed to around 5.5%, reflecting the risk of the X Date now looming potentially less than one month away.

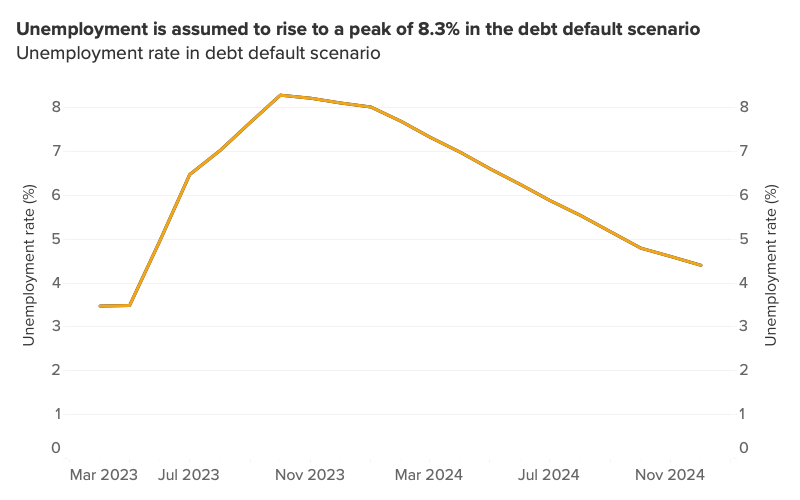

The unemployment rate is also expected to rise substantially in the event of a debt default. Federal government expenditures directly account for a large share of economic activity, and indirectly drive yet more. Federal expenditures alone accounted for 34% of gross domestic product in the first quarter of 2023. Hitting the debt limit would mean the federal government can only spend as much revenue as it receives each month, no longer able to issue debt to finance the running deficit. For context, the federal deficit was over $1.3 trillion in fiscal year 2022. If the 2023 budget shortfall is similar, then spending would need to be slashed by approximately that amount: more than $1 trillion on an annualized basis. Similarly, past research [1] by economists at the Federal Reserve in 2013 showed that the Treasury would likely prioritize payments to cover interest obligations, reducing spending by over $1 trillion, annualized. The equivalent impact would be larger with today’s larger budget deficit.

Such a large reduction in spending would necessitate furloughs among federal and state employees, and likely trigger waves of layoffs at contractors and other employers more indirectly connected to federal spending. The logic of a recession beginning might become self-perpetuating, as consumer and investor confidence fall amid market turmoil, leading employers to trim payrolls.

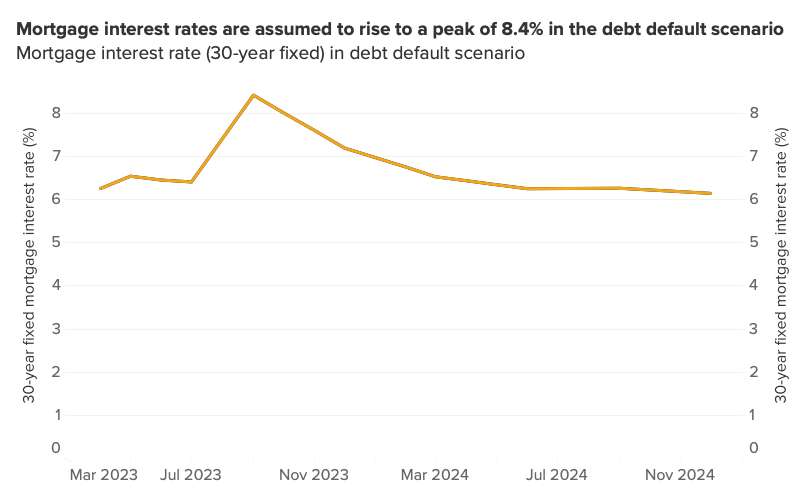

Forecasting the effects of a debt default on the housing market requires monthly time series projections of the unemployment rate and 30-year mortgage interest rate. To construct these, we rely on scenarios published by Moody’s Analytics in the runup to a potential debt ceiling crisis in 2021, which provided the general contour of potential increases to unemployment rates and 10-year Treasury yields. [2] We model the impact to 30-year mortgage rates as a linear projection from the Treasury yields, based on the linear relationship observed over the last 52 weeks as of the time of this writing. [3] We add the predicted shocks to mortgage rates and unemployment rates to our existing baseline forecasts for these variables over the next two years.

The resulting economic scenario is sketched out below: A sharp increase in the unemployment rate starting this summer — jumping from the current level of 3.4% to a peak of 8.3% in October before gradually declining — and an increase in 30-year mortgage interest rates to a peak of 8.4% in September, before declining, as well. Those are in contrast to our baseline scenarios, in which we expect unemployment to only gradually increase very slightly from its present generational-low level of 3.4% over the next year and a half, and we expect mortgage rates to gradually fall somewhat over the same timeframe.

We ran our forecast models for sales volume and price appreciation using the debt default scenario charted above, while holding other key input variables, such as demographics, the same as in our baseline forecasting scenario. [4] In the event of a debt default, existing home sales volume would fall from a projected seasonally adjusted annualized rate (SAAR) of 4.3 million this April to 3.3 million in September – a decline of 23% in housing market activity, both from the current pace of sales and the pace that we predict would prevail in the absence of a debt default crisis. Cumulatively, in the 18 months from July 2023 to December 2024, the decline in sales volume would be just over 700,000 existing homes sold – that is almost 12% of the 6 million sales in that 18-month span we would expect without a default.

The projected impact to home values is more modest: In the debt default scenario, seasonally-adjusted home values are projected to diverge downward from the baseline forecast starting in August, decline by only about 1% from current levels through next February and end up 1% higher than today’s values at the end of 2024. Still, this would reflect a five-percentage-point reduction relative to the baseline forecast, which predicts home values to rise 6.5% in that year-and-a-half timespan.

It appears that home prices remain somewhat insulated from deeper declines due to today’s very low inventory and the especially low flow of new listings so far this year. Higher mortgage rates would likely further discourage homeowners from listing their homes, as they seek to avoid selling in an unfavorable market environment, much like the increase of mortgage rates in 2022 helped to depress new listings. However, if unemployment really rises by as much as assumed here, that could force many homeowners, unable to pay their mortgages, to sell, putting more downward pressure on home values than predicted here.

Note that the lower growth rate of home values would not do much to help first-time home buyers, because higher mortgage rates will offset much of the affordability benefit from the lower purchase prices. In fact, if mortgage rates and home values follow these projected paths, the cost of a mortgage to buy a home valued at the typical national value this September would be a whopping 22% higher than in the baseline forecast scenario; by May of 2024, the mortgage costs would be about the same in each scenario, but with a higher share going to interest rather than principal in the debt default scenario. The exact timing and magnitude are very uncertain, but the general predictions of a modest decline in prices and sharp rise in interest rates combine to mean a net loss of affordability for buyers.

The exact contours of a debt default scenario this summer are unclear, but also unimportant for the conclusion about its impact on the housing market. Any major disruption to the economy and debt markets will have major repercussions for the housing market, chilling sales and raising borrowing costs, just when the market was beginning to stabilize and recover from the major cooldown of late 2022. Like the impact to labor markets, the housing market fallout would represent an unnecessary own-goal at an inopportune moment, when macroeconomic policy makers already have their hands full attempting to cool down inflation without tipping the economy into recession.

[1] If “the Treasury prioritizes its payments to cover all scheduled net interest payments, other federal spending would be temporarily reduced by the following amounts (expressed in nominal terms at an annual rate): $340 billion in nominal federal purchases; $630 billion in Social Security, Medicare, and other transfer payments; and $150 billion in grants to state and local governments.”

[2] “Playing a dangerous game with the debt limit,” Mark Zandi and Bernard Yaros, Moody’s Analytics, September 21, 2021.

[3] For 10-year Treasury yields averaged by weeks ending on Thursdays (“y”), and coincident Freddie Mac Primary Mortgage Market Survey average 30-year mortgage rates (“m”), accessed via FRED at the St. Louis Fed, for the weeks from April 21, 2022 to April 13, 2023, the linear relationship was m=1.44y+1.136. R^2=0.95. The mean squared error of this linear model, within the last 52 weeks, was only 0.019, compared to an MSE of .053 when predicting mortgage rates using the average spread (equivalent to requiring a slope of 1 in the above regression).

[4] This debt default scenario forecast was run in April, using otherwise identical model inputs and parameters to those used in the baseline forecast run in early April, for an apples-to-apples comparison.